Introduction

by Tim Fulford

This is the first edition of the love letters and poems of a woman at the centre of one of the social circles in which Romanticism was shaped. Anna Beddoes (1773-1824) was the wife of the doctor, chemist, poet, political campaigner and social reformer Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808). The Beddoes were friends of Coleridge, Southey, Thomas and Josiah Wedgwood, James and Gregory Watt, and Thomas and Catherine Clarkson. Born an Edgeworth, Anna was connected though family ties and friendships not just to her sister Maria but also to the Darwins and the Aikins. Based in Clifton, Bristol, where her husband established the Pneumatic Institution to research the curative effects of gas inhalation, where Coleridge and Southey planned Pantisocracy and gave political lectures, and where Wordsworth worked on his ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’, Anna was at the hub of a group of intellectuals and experimentalists pioneering new kinds of science, medicine, politics and poetry. She was an unconventional woman, with advanced ideas about women’s conduct and language, and she put these ideas into practice in her intimate correspondence and relationships. Between 1799 and 1809, she engaged in at least three love affairs, each with a man drawn to Bristol by her husband’s innovative medical practice – Humphry Davy (1778-1829), William Wynch (1750-1819) and Davies Giddy (1767-1839). Letters survive from each of these relationships, mainly hers rather than her lovers’, the overwhelming majority being to Giddy. We present them here, in chronological order, fully annotated, and in a format designed to replicate as far as possible Anna’s informal habits of lineation and punctuation. We also present the poems that Anna exchanged with Davy and Giddy, in a separate section except when the dated letter in which the poem was sent survives, in which case it appears in its chronological place among the other letters.

How does a woman brought up in the era of sensibility – the revolutionary era of the 1780s and 90s – write about love and sex, when free of the self-censorship that comes with publication? The love letters of Anna Beddoes are one of the few bodies of writing from the period in which we can access a woman’s romantic and erotic voice unmediated by ‘propriety’. Unmediated by propriety but not uninfluenced by sensibility: Anna Beddoes wrote – and then acted upon – her letters as if she was one of the characters in a Gothic romance or a fashionable love song. Her correspondence did not so much describe her passions and her affairs as bring them into being, first in imaginary form and then in reality. To conservative moralists such as Hannah More, it would have appeared a prime example of the moral danger of reading romantic novels; to radical feminists such as Mary Wollstonecraft it would have illustrated the fixation on attracting men that resulted from women’s lack of education, property and professional opportunity. Anna, she would have judged, was one of those women who ‘waste life away, the prey of discontent, who might have practised as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility’1.

But Anna Beddoes did not hang her head very much; she was an active and strategic writer and an active and strategic lover who explicitly preferred the excitement of the passionate affairs that her writing conjured up to the petty charades and polite reserve of genteel social life. That she did so is perhaps not wholly surprising. Born in 1773, Anna grew up in the ever-increasing and unconventional family of the Enlightenment inventor and reformer Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Among her father’s friends were the freethinking Thomas Day, author of the educationalist Rousseauvian novel Sandford and Merton, and the evolutionist Erasmus Darwin, poet of the sexually risqué Loves of the Plants. Her step-mother Honora Sneyd was the beloved muse of Anna Seward’s poems; her sister Maria was the novelist who wrote Belinda. With this background, it is not surprising that, in 1794, Anna chose for her husband a writer of advanced, revolutionary views. Thomas Beddoes, a disciple of Darwin, had published learned papers on science and medical books on consumption – and he was also a poet and a writer of tales for the poor.

Anna herself was, by her own admission, no intellectual. But nor was she a woman of fashionable, but trivial, ‘accomplishments’ designed to impress at parties. She had not, it was noted, been trained to ‘dance, sing or play on the harpsicord’2. Highly perceptive but poorly educated, she saw herself in terms of the women of sensibility who were the heroines of the contemporary novels and poems she liked to read. August Kotzebue’s Constant Lovers and Charlotte’s Smith Elegiac Sonnets were her chosen fictions; their highly-charged confessions of feeling, disregarding traditional decorum, were her model. She spoke, and wrote, with an unreserved immediacy that, in the revolutionary 1790s, was coded as a kind of radical sincerity. It was startling in its candour and daring in its impropriety. Yet if this was new, Anna had little interest in social reform or political change: her subject was passion and the dramas that women entered by expressing their passion. At times she acted like Marianne in Sense and Sensibility; at other times she sounded like Jane Austen writing about Marianne.

Anna certainly wrote freely about her passion – and acted on her writings. Her love letters and poems give an unparalleled view of how a woman of sensibility fashioned herself, and the men she attracted, as lovers of a new, Romantic, kind. The letters begin in the year 1800 – six years into her marriage to Beddoes, by which time she had become lonely and frustrated. While solicitous about her health and respectful of her freedom, Beddoes was consumed by the man’s world of medical practice, scientific experiment and revolutionary politics. Thirteen years older than she, he was, in her father’s words, a ‘little, fat democrat’3. He lacked social graces; he wheezed. So in autumn 1798, when a boyishly handsome and strikingly brilliant assistant moved into the Beddoes’ household in Bristol, Anna soon developed the intimacy with him that she lacked with her husband. Humphry Davy (1778-1829) was a Romantic youth – an effusive poet and an innovative experimentalist consciously aspiring to the role of genius. He had already learned that the cliffs and bays of his native Cornwall were an ideal stage for sublime, self-projective verse; now he and Anna walked together in the sublime Avon Gorge and their intense conversations led to declarations of feeling for both nature and each other – made in person and in verse. In fact, it is not too much to say that it was in poetry that they fashioned their relationship, creating versions of each other and of themselves that they tried to live out. This poetry aimed at rapture; it idealised love and exalted the feelings of the lover. Highly-wrought sensibility – feeling revealed through the quivering body – was what it valued and in this respect it was in the mode popularized by Charlotte Smith and Mary Robinson and, in Davy’s case, by Coleridge and Wordsworth. One of Davy’s poems begins ‘Anna thou art lovely ever / lovely in tears / in tears of sorrow bright / Brighter in joy’. One of Anna’s poems ends ‘Love, to this heart, his image gave – / This heart, shall bear it to the grave’.

The couple must also have written letters to each other, at least after March 1801 when Davy left Bristol and took up an appointment at the Royal Institution in London. But almost none of that correspondence survives, although hints in letters that Davy sent to his friends John King and William Clayfield (both of whom also worked for Beddoes) suggest that it may have been Anna whom he sporadically met for passionate liaisons. A letter that has been preserved reveals that they saw each other in Bristol in December 1804, by which time Davy had become the talk of fashionable London – his lecture performances especially popular with young women. On this occasion, Davy tried to end the relationship; he gave Anna his picture as a memento but asked her to forget him as a lover. This led her to send an allegorical poem about the appeal of his looks to other women. The poem ended with rueful irony about her own position as a forgotten lover:

Those eyes with liquid lustre bright

In softer eyes have quenched their light

Eyes, that withdraw their timid beams

And only dare to gaze in dreams.

And yet regardless of thy power

Some tender maid each changeful hour

Is doom’d in silent grief to pine

Or paint it, in the glowing line –

‘Or paint it’: picture-making and poetry are here an expression of lovestruck grief; Anna, as poet, is merely one of many ignored ‘maids’ left writing about what she cannot have.

In the letter that accompanied the poem, Anna was typically spontaneous – thinking, and changing her thinking, as she wrote: it was this quality that gave her letters their lively intimacy. She was also untypically reflective: looking at Davy’s portrait led her to analyse the difference between art and life, and also between the picture made by the portraitist and the pictures conjured by her memory. Davy’s image on paper was suggestive of the difference between his past presence and his present absence – it signified temporal loss, spatial distance, and the lack of the mental and emotional liveliness that he evinced in person, then and now again, when once more she met him in person:

it puts me in mind of the days that are past; not then in [word missing] we quarrelled but others which we passed in mutual confidence – the impression of these seem far from wearing out, seems to sink deeper and deeper into my mind – the features are like but the expression of the eyes is not the same as yours; when first I saw the print I thought the face handsomer than yours, but you love caprice. I have changed my mind and now cannot find half the expression that ought to be. I like the picture on another account – and if you cannot find out what it is, & have any desire to know what I will tell you – pray do not forget to send me your poems – and pray, pray do not forget me altogether – I will not ask you to write to me because I hope and believe your time is far better filled up even in recreation – your mind appeared so vividly alive the last time I saw you that it roused the almost [one word illeg] spark of ambition in my bosom – Farewell my heart is I hope improved if my understanding is not – I know not what reason it is but I cannot write, or think of you without the most melancholy sensations – adieu

‘Do not forget to send me your poems’. When the prospect of future meetings was to be forbidden, when a mutual love was to be forgotten except in separate memories, then poetry, the medium of their relationship, was a more evocative souvenir than a portrait. What would survive of them were words and words’ ability to generate feelings, even if those feelings could not now be shared and had, for that reason, turned melancholy.

A letter as poignant as this was not to be destroyed, as Anna suggested it should be. Davy kept it, although he did not keep others, and he also, if his own poems are reliable evidence, continued to meet Anna, as well as to yearn for her – married though she was, until 18074. Most of his verse for Anna looks back nostalgically on 1799-1801 –

the days

When first through rough unhaunted ways

We moved along the mountains side

Where Avon meets the Severn tide

When in the spring of youthful thought

The Hours of Confidence we caught

And natures children free and wild

Rejoiced, or grieved, or frowned or smil’d

As wayward fancy charmed to move

Our minds to hope, or fear, or love.

Viewing their relationship from the changed perspective of temporal and spatial distance, Davy wistfully reckons the difference between the time when ‘Alone she filled the mind / A vision of delight / In which all natural charms / Of motion colour form / Were kindled into life’ and the present, in which Anna remains only as a trace in his perception of the landscape:

in Natures forms, I see

Some strong memor< i >als of thee. –

The autumnal foliage of the wood

The tranquil flowing of the flood

The down with purple heath oer spread

The awful Cliffs gigantic head,

The moonbeam in the azure sky

Are blended with thy memory.

Anna’s poetry also looked back ruefully to the scenes of their shared passion, realizing, from a perspective only possible owing to distance and loss, how precious they had been:

that sequestered favourite glen

Unhaunted by the buzz of men.

Or the lone summit of the wood

That brooded o’er the dusky flood –

Of these my harmless joys bereft

Faint is the sunshine that is left. –

Yet still I glow with feelings warm

The wreck of many a mental storm,

These, are for thee, as fresh as true

As in my earliest days I knew. –

And oft I think upon the time,

Ere I had stepp’d beyond my prime,

When thou just bounding into life

Alike unknown to grief or strife

Panted with transport for the hour.

When the whole world should feel thy power.

Remembering their youthful passion as a period of bliss unspoilt by the effects of time – effects of which she is now only too aware – Anna reconciles herself to Davy’s departure. She sees herself now as ‘a Being void of aim’, alone, in contrast to Davy who is admired – not least by women – in a wider world in which he was becoming successful. Her part as a woman is to be bereft, after having nurtured his early genius by her love; his, as a man, is to become powerful and famous. Here, Anna echoes Charlotte Smith’s voicing of women’s experience as lovers; Felicia Hemans and Laetitia Landon would later take up the theme.

Davy’s voice was more Wordsworthian. His tendency to displace his lost lover into the evanescent forms of nature culminated in a lament that he drafted after Anna’s death in 1824. Entitled ‘Dies Irae’, the poem begins with Davy remembering, like Wordsworth mourning Lucy, that

Nine years, a joy, a pure delight

She dwelt upon my raptured sight

When present: and in absence gave

A hope which made my heart her slave.

If derivative of Wordsworth’s Lucy poems, this verse is not a pastiche but a remodelling through which Davy struggles to articulate what his love had been and what it meant now that Anna was dead. He did not publish the poem; nor did he communicate it to friends. It was a personal exercise: writing Anna as Lucy enabled Davy to find a plangent verbal shape for his grief and anger –

< Alas, her form of loveliest > mold

Is now insensate dark & cold

But the pure & sacred fire

Which warmed her mind can not expire,

It kindles, breathes & lives with me

In every form & memory….

That he continued to write verse about Anna long after their affair ended, and also after she died, suggests that it was in love poetry (her love poetry and his own) that the relationship – that Anna – was shaped and that it was in poetry that it – and she – could be recollected. Davy’s memorializing verse made her an internalized ghost or informing presence who could be sensed because she was made articulate in the images, rhymes and rhythms of poetry that echoed the poetry they had exchanged years before.

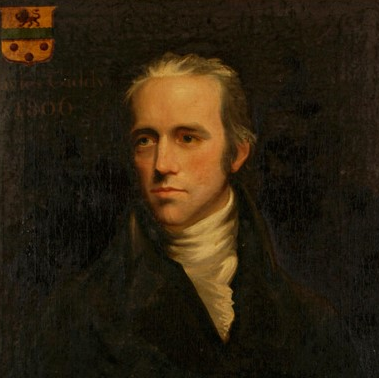

It was less as a poet and more as a letter writer that Anna forged a love affair with another of her husband’s colleagues. Davies Giddy was Beddoes’s former student, then friend. He was also Davy’s early mentor – living near Penzance, Cornwall, as the young Davy had done. In August and September 1800 Giddy was in Bristol being treated by Beddoes but was well enough to socialize with Anna and her sister Emmeline. Aged thirty-three and only six years older than Anna, Giddy was more personable and virile than her husband but less brilliant and Romantic than Davy. He possessed qualities that Anna, who saw her own character as weak, admired: he was stable and determined, though kind and considerate. He took on responsibility, even when doing so was dangerous or unpleasant: in his position of High Sheriff and Deputy Lieutenant of Cornwall he had to face down angry crowds rioting over the price of food and persuade reluctant farmers to bring their grain to market at affordable prices. He was a bachelor; he came from a small, tight-knit family; he honoured and guided his father, mother and sister, who all lived with him. Anna’s upbringing, in contrast, had involved a remote, often absent father and the deaths of her mother, her step-mother and several siblings.

Anna’s correspondence with Giddy developed after his return to Cornwall; she played the role, at first, of a flighty and flirty friend determined to tease him out of his sensible reserve. Soon, giving him the name ‘brother’, she began seeking his guidance about her and her friends’ intimate affairs. Divulging the details of her romantic involvement with men other than her husband, she adopted a radical sincerity that had the effect of making Giddy a voyeur of what most people at that time would have judged to be frankly scandalous behaviour. She sought his advice about a ‘scrape’ she had got herself into with an older man, William Wynch, who had been staying at Bristol for treatment by Beddoes. Unfolding details about Wynch’s ‘cruel’ wife and unhappy daughter (who had married an abusive fortune-hunter), Anna revealed that she had become drawn into a relationship with him. She and Wynch had exchanged love letters and poems; they had sent each other love tokens; he had arranged to leave her a considerable legacy in his will; they had even promised to marry each other if their spouses died. Could Giddy suggest what she should do? He advised her to stop writing to Wynch and to reclaim her letters, poems and love tokens; she then ran past him a draft of the letter she was composing to end the relationship (his emendations aimed to make it more decisive). Effectively, Anna had now generated an intimate, secret correspondence with Giddy on top of the intimate, secret correspondence with Wynch; by doing so she had also signalled to him her openness to conducting love affairs outside her marriage.

This may have been a strategy to attract him, for whether or not she intended him to be, he was titillated as well as emotionally involved. Invited to resolve her passionate and – she hinted – adulterous entanglement, Giddy found himself a confidante, privy to information that her husband, his best friend and regular correspondent, was ignorant of. An awkward triangulation had come about, and an unspoken desire been aroused – creating a tension that would not come to a head until the writers were together in one room. The relationship, that is to say, grew because of the physical absence that the intimate letters simultaneously bridged and emphasized. Anna, from a distance, stated her sexual availability directly: she’d rather be the mistress of a man she loved than a wife, she wrote. Thus Giddy was put on notice, though on paper he continued to offer sober advice: abandoning social duty for immediate pleasure, he observed, might bring excitement but would lead to great pain in the end (a prophecy that Anna and he came to prove true but that was less daunting for her, needing emotional excitement as she did, than for him). He recommended steady application to study as a way Anna might ground herself and improve her mind – learning languages, reading sober and informative fare such as Gibbon and Herodotus. Anna, however, used literature to model how to act and feel as a lover: Kisses, Robert Dodsley’s collection of erotic songs, was her recommendation to him.

In September 1803 Anna paid a visit to Giddy in Cornwall without her husband. Prepped by their letters, she became closer to him, riding horseback behind him, encouraging him to tell her all he knew about the landscape. He accompanied her on part of the long way home to Bristol. At Ivybridge, standing alongside each other on the rustic bridge in a picturesque dell, there was a frisson. As Anna portrayed it in the letter and poem she sent him few days later, ‘you have excited in me a great ambition to improve myself, and I am determined I will no longer remain in that scandalous ignorance, in which I have been so long tremblingly alive – but hope by exciting my stagnant faculties, to overcome the obstacles that obstruct my passage – then instead of a sleepy pool, my mind will be like the animated foaming flood at Ivy-Bridge’:

Clear shone the sun in the fresh of the morning

The lingering dew-drops the valley adorning.

Green over the bridge hung the ivy, and shrouded

The swift rolling torrent, with foam softly clowded. -

’Twas here as enraptured I gazed on the scene,

Unconscious of aught but the present sweet hour

The steep winding pathway a coppice between,

Whose delicate branches entwined in a bower

’Twas here that my bosom was aching with sorrow

’Twas here that it felt every joy it could know

But flown was its joy by the dawn of the morrow,

And this deep-rooted sorrow, ah! When shall it go!

And why was this bosom so tortured with sorrow?

And why flew its joys by the dawn of the morrow?

The source of my sorrow, ye never shall know,

This deep rooted anguish that never shall go –

Here Anna takes the role of entranced nature-lover, her body feelingly alive to the scene – only to hint, not too subtly, that, like the narrator of Smith’s sonnets, and like many a Gothic heroine, she is afflicted by a secret sorrow that her joy in natural beauty can only briefly allay. That this sorrow afflicts her bosom hints at its passionate, sexual nature: in this too, Anna echoes the lovelorn figures depicted by Smith. Unlike Smith, however, she writes directly to a would-be lover, so that what might be a note of tragic resignation – ‘The source of my sorrow, ye never shall know’ – becomes a tease. Giddy is being challenged to discover the source and to solace the anguish. Anna followed this with a letter of irreverent banter that teased him more comically: ‘And now Mr ill-natured please to tell me whether you often ride out, – or whether you sit pondering with your long (sacred) hair <hanging about your pale face> in your own room, whether you often open your beaureau, look at your bees, and talk to Tom – answer these, and a thousand more equally impertinent questions – and yet then, I will not forgive you for burning the letter – but I shall punish you rarely for this – you could not imagine, fine as your imagination is, what a sheet of wonders I was going to have sent you – but now I never shall’.

Giddy came to discover those ‘wonders’ in person eight weeks after Anna had left Cornwall, arriving at Bristol on 29 November 1803. With her husband away, he and Anna had time to themselves. Giddy noted in his diary for 1 December ‘The evening of this day rather remarkable': their tête-à-tête had moved from intimate conversation to the unfolding of the ‘secret’ that Anna had been leading him on to uncover. After their passionate kissing and petting, Anna sent a letter responding remorsefully to his remarking that the occasion might soon be forgotten in his absence: ‘you may love me, but at the same time you secretly despise me and to be despised by you is worse than every thing – if I am less kind to you, perhaps I may regain what I have lost in your esteem, to lose what I have gained in your love I can, at least I hope can bear on these conditions – no, not even your persuasive tongue nor even your still more persuasive eyes can make me see myself in any other light than what I really am – a good for nothing woman’. Here her anger proceeds from a moment of illumination in which she imagines herself in others’ eyes as a compromised loose woman and then owns that view. Yet by sending the bitter and accusatory recognition to Giddy she intensifies the emotional drama that her letters create and tacitly invites him to reassure her. Characteristically, she ends the letter by a gesture that invites him to elicit more intimate self-revelations from her: ‘I have a great deal more to say to you but I cannot bring myself to go on’.

Giddy remained in Bristol throughout December 1803, visiting both Anna and her husband with his father and sister. This must have been a period of clandestine intensity, as he and Anna so often met in the presence of relatives and friends whom they did not wish to upset. In January 1804, Giddy took his party to Oxford, so that his family might see where he had studied – he took them on a tour of Beddoes’s old chemical lecture theatre. Anna came too, though it appears this may not have been part of his plan. He returned to Bristol with her on 20 January; her husband was away seeing to a patient; on 22nd they shared a bed for the first time. Beddoes returned on 23rd, meaning the lovers’ communication was then confined to the billets doux they exchanged and to the almost daily walks they made together in Clifton and Leigh Woods. Anna’s letters from this time are charged with romantic and sexual feeling that is only sharpened by the knowledge that they are unlikely to be able to stay together. On 26th she wrote ‘When I go to Bed I shall fancy you . . . beside me with your head on my Pillow & your lips close to mine – If I can go to sleep with this sweet thought I shall be quite happy – will you think of me too, my dearest love?’. Still fashioning her life in terms of fiction, she refers him to a sonnet by Harrington about the temptations of lips, eyes and blushes. On 27th, her feelings led her, it seems, to propose that she would abandon husband and children and live with Giddy, in open adultery – a move that would have ended his friendship with Beddoes, severed her from her children, and destroyed both their reputations, leading them to be ostracised. Giddy wrote in his diary ‘before we set off a very singular occurrence happened to me greatly to my mortification’. On 30th she apologised for the distress caused and tantalised them both by imagining the life she could not have with him as her husband:

My very dear Davies, my sweet Friend, you have been greatly agitated, you have suffered, & I have been the wicked cause of it – is there any soft and gentle name more tender than an other? for by that I would call you — alas there is one – but it can never be pronounced by these lips – never, never – where are the lips that will glory in this enchanting name – where are the lips that will inhale your sweet kisses, where is the Bosom that will be pressed & loved as mine has been – is it warmed by a Heart that will beat time with all the varieties of your excellencies – oh God shew me this woman and I will give up all my happiness.

Tellingly, given the literary nature of their relationship, Anna imagines this scenario as the ability to pronounce a name (‘husband’) that she cannot herself explicitly write, things being as they are. An open, direct speech can be glimpsed but not used; their love language remains a delicious but also limited writing of innuendo and allusion.

By August 1804, with distance taking its toll, Giddy was finding it hard to believe that Anna’s feelings were sustained. She answered his suggestion that she now loved him less by an erotic fantasy that harked back to their embraces and promised more intimacy still, yet also acknowledged that it was in the imagination that these delights existed:

I some times tremble with desire that never can be justified. I would not exchange this sweet agonizing feeling, for any thing but a reality that never will be my lot – all that has been painted by the warmest imagination I have felt – all but the reality – and how well I know that all that can be described of this bewitching passion would be experienced by us – When all is dark I imagine you beside me I fancy you press with firmness the little Bosom you are so fond of – your soft hand wanders over my whole person, our limbs entwine together – but nothing more – no I never have taught you of my love.

This is as much a piece of auto-eroticsm – Anna ‘frigging [her] imagination’5 by writing – as it is enticement. ‘Come hither’, it says, but knows the journey is too long for that to happen any time soon. Yet it is one of the few texts of the period in which we encounter a woman’s erotic voice (outside fiction, which could not be so sexually explicit). Anna excites her lover and herself by portraying her bodily pleasure and mental excitement with unashamed frankness.

In December 1804 Anna met Davy and reflected ruefully on the dimming of their relationship and her past ‘unkindness’; she wished him well on seeking a wife, as well as sending him the mournful poem I discussed above. Meanwhile, she continued writing, and sending poems, to Giddy. By March 1806, however, their tone had changed: the verses Anna sent let Giddy know her ‘heart did grieve’. Then on 25 November Anna sent a longer poem, aligning herself with its Gothic heroine – an abandoned lover. It ended with a self-dramatising and self-pitying dismissal:

Go triumph o’er a heart like mine

Forgotten leave me to repine

And seek a wealthier fair!

But lead her not beneath the Tower

Nor woo her in the moonlight hour

’Twould drive me to despair

————

A trembling ruin is my heart

My love like ivy will not part

But clings so closely o’er

’Twill form a shelter sweet for me

Where all unseen I’ll think on thee

Till I shall be no more. –

And a sarcastic note: ‘If you have never seen this little Poem tell me how you like it – I copied it out thinking it might perhaps please you – but then these kind of trifles are only agreeable when one is in the humour for them’. Here, then, the poem acquired a pointedness; it became a clever rebuke rather than an example of what Anna Seward had called, in Charlotte’s Smith verse, ‘hackneyed scrap[s of dismality’6. It had been provoked, it appears, in December 1805 or early 1806, when Anna had joined Giddy in London visiting his sister. Giddy had told Anna he wanted to withdraw from their passionate relationship so as to be free to find a spouse. From then on, Anna’s letters exhibit her struggle to overcome her suffering, anger and jealousy by remembering her affection for him and by striving to be generous. In January 1808, as Giddy visited Bristol after having begun courting the woman he would marry – Mary Gilbert – Anna excused herself for the ‘the petulance & indeed aversion which I sometimes betrayed to you’ and confessed that ‘I am not the person I was but am so irritable that I deserve neither friend – or even the shew of friendship – the fact is that I am highly disgusted with myself for having suffered mental feelings to have been so mastered by such as are unworthy both of us’. His gentleness and apologies calmed her; she then felt able to free him to enjoy the family life that she already had, although not without confessions of the hurt she felt, despite herself. They kept writing to each other even as Giddy’s wedding approached in April 1808, and even sent each other letters in code, as if preserving their affection from his future wife’s eyes. Though Giddy’s letters are mostly lost, it’s clear from Anna’s that he put her under strain by anxiously soliciting proofs of the continuance of her affection: her coded letter declared ‘the word love from you flushes7 my cheek’. He could not bear to be without her friendship and her approval even as he gave himself to another woman, and he made matters still harder for Anna by confiding in her his fears that he would not be happy with his wife.

Anna, with great self-control, reassured him, and after some months she re-emerged as a chatty family friend, sending letters full of news, no longer claustrophobically centred only on her feelings and their relationship. In October, she was excited to meet Giddy again when he came visiting, although there were still tensions when they met, perhaps because Giddy sometimes distanced himself in fear of raising old resentments, causing Anna to protest that she felt nothing but kindness towards him. The saddest of these occasions produced one of the last letters in this edition – written a week after her husband’s unexpected death. Giddy had come to Bristol to help in the aftermath; there had been a scene; he had withdrawn; Anna sent a note across town after him: ‘I am alone – & perhaps can convince you of what I never thought you could doubt – how immensely I feel obliged & how grateful I am for your kindness / Do you wish to add to my present sorrow by taking from me your affection’. She must have recognised the sad irony of the timing: if Thomas Beddoes had died a few months earlier, or Giddy married a few months later, would she have been able, after all, to call Davies ‘husband’?

Beddoes’ death utterly changed Anna’s life. Without her husband’s income and unable to provide for herself, she was left in reduced circumstances. With four children under the age of ten, and now in her mid-thirties, she found no prospective husband eager to take her on. The Bristol house in which she had lived, and fallen in love with Davy and Giddy, had to be sold and the proceeds carefully managed. Giddy took charge of her financial affairs and continued acting for her children when she died, in Florence, in 1824. So there were more letters. But these were kindly business letters: the days of writing to each other as lovers – prospective, actual, retrospective – were over.

Notes

1. A Vindication of the Rights of Men, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, ed. Janet Todd (Oxford, 2008), p. 230.

2. The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, ed. Tim Fulford and Sharon Ruston, 4 vols (Oxford, 2020), I, 36.

3. The view of Richard Lovell Edgeworth, in a postscript he added to Maria Edgeworth’s letter to Margaret Ruxton, 21 July 1793, National Library of Ireland MS 10166/7/105.

4. He also saw her in 1811 but by then they were no longer romantically involved.

5. Byron, describing Keats’s poems. Byron’s Letters and Journals, ed. Leslie A. Marchand, 13 vols (London, 1973-94), VII, 225.

6. Letters of Anna Seward, ed. Walter Scott, 6 vols (Edinburgh, 1811), I, 287.

7. In error, she coded the word as ‘fdushes’.

Further Reading

Wahida Amin, The Poetry and Science of Humphry Davy. PhD dissertation, 2013, https://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/30795/1/Wahida_Amin_-_The_Poetry_and_Science_of_Humphry_Davy_-_23.01.14.pdf

The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, ed. Tim Fulford and Sharon Ruston, 4 vols (Oxford, 2020).

The Davy Notebooks Project https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/humphrydavy/davy-notebooks-project

Rachel Hewitt, A Revolution of Feeling: The Decade that Forged the Modern Mind (London, 2017).

Maurice Hindle, ‘Nature, Power, and the Light of Suns: The Poetry of Humphry Davy’, https://mauricehindle.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Nature-Power-the-Light-of-Suns-essay.pdf

Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science (London, 2008).

Mike Jay, The Atmosphere of Heaven: The Unnatural Experiments of Dr Beddoes and His Sons of Genius (London, 2009).

A. C. Todd, Beyond the Blaze: A Biography of Davies Gilbert (Truro, 1967).

For information about citing and reusing material on this website see How to cite