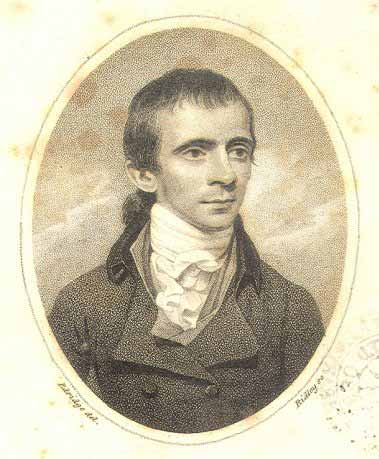

Biography

As a boy Robert Bloomfield worked as farm labourer in the Suffolk village of Honington before moving to London and becoming a shoemaker. In a tiny, backstreet East End garret, he learned to compose poetry, silently, in his head, amid his workmates’ chatter. In 1798, he wrote down the verse that he had memorised and set about getting it published. London booksellers took no interest until his brother showed the manuscript to a country gentleman, Capel Lofft, from Robert’s home county. Lofft was a poet and critic with connections in the publishing world. He spruced up the manuscript and got it published, in 1800, as The Farmer’s Boy. Unexpectedly, this four-book Georgic evocation of life and labour on an English farm became a massive hit. In Bloomfield’s lifetime, it went through fourteen official editions, was translated into Latin, and sold an estimated 51000 copies – putting it on a par with Childe Harold and The Lay of the Last Minstrel as one of the bestselling poems of the Romantic era. This popularity lasted: new editions regularly appeared until 1877; only in the twentieth century did interest decline. Admired by poets, including Southey and Wordsworth, Bloomfield was also a seminal author for labouring-class writers, including John Clare; his representation of Suffolk, meanwhile, influenced John Constable’s art.

Bloomfield’s next collections, Rural Tales (1802) and Wild Flowers (1806) were also popular sellers, and show him in dialogue with Lyrical Ballads – using narrative poems to revalue the experience and feelings of villagers. By this time, buoyed by commercial success, he had given up his shoemaking trade and become a professional author. He was locked in struggle to escape the well-meaning but condescending editing of his work by Capel Lofft. Literary independence, finally achieved when he gained control of the text of his Collected Poems, came at the price of exposure to the vagaries of the publishing market. His 1811 tour poem, The Banks of Wye, was not a big seller and in 1813 his publisher went bankrupt: at a stroke Bloomfield lost most of his income. He moved from London to cheaper and quieter lodgings in a Bedfordshire village, where, increasingly afflicted by illness, he became gradually impoverished. What he managed to write and publish after this move was remarkable, but not commercial. His children’s story Little Davy’s New Hat (1815) contains a stinging portrayal of the mental and physical costs of grinding rural poverty; his final verse collection May Day with the Muses (1822) imagines a reformed rural world in which the self-representation of villagers is valued by their social superiors: the squire is led by his labourers.

Bloomfield died in 1823 in such poverty that his books, effects and furniture had to be sold to provide for his family. Forgotten by the public, he was lamented by John Clare, who called him ‘the most original poet of the age & the greatest Pastoral Poet England ever gave birth too’.